A Failed Lab Experiment to Produce Quinine Leads to Purple Dye

The year was 1856 and a young man of 18 was attempting to chemically synthesize quinine after having heard, in a passing comment from his mentor, of its importance. At the time, quinine was considered the only viable treatment for malaria. And with 1850s England pushing into Africa as well as being in the midst of the Crimean War, quinine was in high demand. Unfortunately, natural quinine came from the bark of a Peruvian tree. The feverish hunt for a synthetic equivalent was therefore underway.

Background

The mentor was renowned German chemist August Wilhelm Hofmann. He became the first director of London’s Royal College of Chemistry only nine years earlier, in 1845. Amongst his many accomplishments include his discovery of formaldehyde. Moreover, Hofmann was distinct because he valued the practical use of chemistry over the science’s theoretical problems. As such, he placed a higher premium on experimental chemistry and its industrial applications.

Interestingly enough, Hofmann was not very competent in the laboratory. Hence, he became very skilled at finding exceptional assistants who could do the experimental work for him. Hofmann had a florid style of speaking that often inspired enthusiasm amongst his students. One such student was William Henry Perkin.

Perkin came from humble beginnings. His father was in construction, for instance. Their home was located in London’s East End – a region described as the ‘Land of the Cockney’ and synonymous during the 19th century with overcrowding and low wages. Perkin, however, had a talent and love for chemistry. By age 15 he began attending the Royal College of Chemistry. Perkin’s precocity soon caught the eye of Director Hofmann, and the boy thereby became one of Hofmann’s lab assistants.

The Fateful Day

While on Easter break in 1856 at his family home, Perkin decided to independently conduct a lab synthesis of quinine from an inexpensive coal tar waste called aniline. But he failed to produce synthetic quinine after several attempts. Instead, all he could get was this mysterious dark sludge, that turned purple when he dissolved it in alcohol. Undeterred by his “failure,” Perkin realized that his accidental synthesis of a purple compound was commercially promising.

That Exclusive Color

But why did the failed experiment prove auspicious? Prior to Perkin’s experiment, purple as a hue was difficult to come by. Only the wealthiest ranks of society could afford it, which explains why it was often associated with royalty and the elite class.

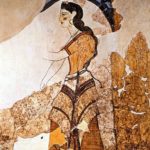

Purple dye originated from Tyre, a city founded by ancient Phoenicians and now situated in present-day Lebanon. The purple dye, or Tyrian purple, was made by a foul-smelling and labor-intensive process of crushing more than 10,000 murex sea snails (shellfish of the Muricidae mollusk family) just to produce enough tint to dye a robe weighing 2 pounds. Tyrian purple was thereupon called “royal purple” or “imperial purple” because it was a hue that only the nobility could afford.

Both literature and history are rife with purple’s juxtaposition with status and influence. According to the King James Bible, for example, “There was a certain rich man, who was clothed in purple and fine linen…” (Luke 16:19). Then, too, King Solomon, while building his Temple, commissioned Phoenician artisans who, in turn, assisted with making the curtains in the Holy of Holies “of blue, purple, and crimson yarn and fine linen…” (2 Chronicles 3:14). Homer’s The Iliad likewise characterized the belt of Ajax as being purple, whereas in The Odyssey Homer depicted Odysseus’ bed with purple blankets. Similarly, historical records chronicle Alexander the Great luxuriating in purple robes. Even Shakespeare wrote of how Julius Caesar enjoyed himself on Cleopatra’s royal barge, “Purple the sails, and so perfumed that the winds were lovesick with them.”

During Caesar’s reign, the caliber of a Roman male citizen was recognized by eyeing his garment – for his rank and authority were proportionate to the number of purple emblems he sported. An infant born to any reigning Roman emperor was distinguished as having been “born into the purple.” On these grounds, by the time of Nero’s reign (54 – 68), a decree was issued promulgating all-purple robes as exclusive to the emperor, anyone else who wore those colors would be executed. Still, there is the anecdote of how purple dye was too expensive for the tastes of Roman emperor Aurelian (reigned 270 – 275), so he forbad his wife from purchasing a silk shawl of Tyrian purple.

Purple as a symbol of prominent status was understood even in the art world. Christ, the Virgin Mother, and even seraphim were portrayed in fabrics of purple. Monarchs, like Emperor Justinian I and his wife Empress Theodora, featured in Tyrian purple on the mosaics of the Byzantine era. In many ways, art as visual media helped to solidify – especially in the cultural subconscious – purple’s association with prestige.

The exclusivity associated with purple likewise had bearing during the reign of the last Tudor monarch. In 1574 a Sumptuary Law – designed to restrict the sumptuousness of attire so as to curb extravagance while simultaneously protecting fortunes and delineating the different levels of society – was enacted that proclaimed:

None shall wear in his apparel: any silk of the color purple, cloth of gold

tissued, nor fur of sables, but only the King, Queen, King’s mother,

children, brethren, and sisters, uncles and aunts; and except dukes,

marquises, and earls, who may wear the same in doublets, jerkins, linings of

cloaks, gowns, and hose; and those of the Garter, purple in mantles only.

Other avenues for producing purple were sought because the murex snail method was outrageously expensive. Some alternative pathways included relying on such natural resources as lichens, Madder root, even bat guano. The guano proved an unappealing mess, and the other natural methods did not produce the quality of purple that murex could bring. They either faded in the wash or under the sunlight. By contrast, murex-made Tyrian purple lasted far longer than the others.

Serendipity’s Repercussions

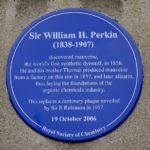

Against this backdrop, young Perkin’s accidental synthesis of a purple compound was a pivotal moment – for he knew he could make the exclusive hue widely available to everyone, including both the middle and lower classes. He therefore capitalized on his “error” by promptly patenting the dye he had synthesized and so gave birth to the modern chemical industry at the tender age of only 18.

Perkin initially branded his dye the name of “aniline purple” and even “Tyrian purple.” His manufacturing process proved to be more feasible, quickly making for him lucrative financial gains. And, when the Empress Eugenie of France, consort of Napoleon III, found the color to her liking, this endorsement gave further commercial boost to Perkin’s dye.

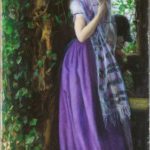

In 1859 the color’s name was changed to “mauve” (an homage to the French word for a purple flower); accordingly, chemists called the dye compound “mauveine.” Mauve became a fashionable color that everyone clamored for and could not get enough of – on account of how rare it had previously been because of the difficulty involved in its production by traditional methods. By the time Queen Victoria’s Jubilee arrived in 1887, she chose to wear a silk gown of mauve – thus becoming the first monarch at a major celebration to wear something in purple that was not produced by the murex mollusk. The murex market, which had lasted for over a millennia, consequently destabilized; by the twentieth century it faded into history. And, just as Prometheus brought the knowledge from gods down from Olympus to spread amongst mortals, shades of purple and mauve took hold like wildfire amongst the general population. Even artists began using purple in images of commoners, no longer reserving it for the upper class.

Meanwhile, Perkin’s accidental discovery led to the formation of an entirely new industry devoted to mass production of artificial dyes. Indeed, Perkin’s mentor, Hofmann, followed the trend with the creation in 1863 of his line of dyes called “Hofmann’s violets” – a range of purple hues heavily patronized by the public so that Hofmann likewise enjoyed commercial success. And, as the dye industry burgeoned, it proved crucial to the advancement of medical research – especially in microbe-staining processes to help researchers identify pathogens like tuberculosis, anthrax, and cholera.

Over the years, Perkin would later perfect the method called the “Perkin synthesis,” a technique used in the manufacture of perfumes and fragrances. Naturally, the synthetic scent and perfume industry also owes much to Perkin, the man who, at 18, had accidentally stumbled upon a revolutionizing breakthrough. Today, the United States has an accolade named after Perkin – the SCI Perkin Medal – it is the highest possible award in the American chemical industry.

Photo credits: (1) That was a Piedmontese, painting by Arthur Hughes 1862 — from the website Tate.org.uk; (2) August Wilhelm Hofmann — from the website orden-pourlemerite.de; (3) William Henry Perkin — from the website ChemHeritage.org; (4) Emperor Justinian I — from Oxford University Press; (5) Murex seashell — from sites.google.com/a/brvgs.k12.va.us; (6) Oldest known murex-dyed textile, 5th-4th century BC in Persia — from State Hermitage Museum; (7) Fresco at Akrotiri of the Priestess, on the island of Thera circa 1550 BC; her dress features Tyrian Purple — from Robert R. Stieglitz, “The Minoan Origin of Tyrian Purple”; (8) Phoenicians trading Tyrian Purple as seen in a painting by Frederic Leighton 1895 — from Bridgeman Art Library; (9) the Peter Paul Rubens painting depicting the legendary discovery of murex (some say the person is Heracles, while others say it is the Phoenican god Melcarth); the dog is an allusion to the dog star Sirius, for murex is harvested in spring when Sirius is in the sky — from a Giclée print on Art.com; (10) Empress Theodora — from Bridgeman Art Library; (11) Emperor Justinian I mosaic in San Vitale, Ravenna — from the website of uncp.edu; (12) Another example of Emperor Justinian I depicted in a robe of Tyrian purple — from Bridgeman Art Library; (13) Another view of Empress Theodora and her retinue — from the website of uchicago.edu; (14) Madonna and Child Enthroned by Giotto di Bondone — from the website Quizlet.com; (15) Seraph from Resurrection of Christ by Raphael — from Wikipedia.com; (16) Charlemagne’s shroud made of gold and Tyrian purple by way of Constantinople — from Wikipedia.com; (17) Fedor Rokotov Portrait of Catherine II the Great of Russia, 1770, oil on canvas, the Hermitage, St. Petersburg — from the website ArtyFactory.com; (18) British King George III and Queen Charlotte in Kew Gardens, with the Queen in purple — from the website of Explore-Kew-Gardens.net; (19) Charles of Bourbon dressed in royal purple, oil painting 1725 — from the website Archaeology.About.com; (20) Marie Antoinette at age 12 by Martin van Meytens — from the website of Polyvore.com; (21) Franz Xaver Winterhalter’s portrait of Princess Maria Carolina of Bourbon, 1846 — from Commons.Wikimedia.org; (22) Napoleon I at Fontainebleau, 31 March, 1814, by Paul Delaroche — from the website of Napoleon.org; (23) Imperial State Crown of Britain — from the website JewelryGemsAbout.com; (24) Empress Eugenie of France — from the website of bbc.co.uk; (25) Franz Xaver Winterhalter’s portrait of Empress Eugenie of France — from the website FranzXaverWinterhalter.Wordpress.com; (26) Queen Victoria presenting a Bible — from the website of lasalle.edu; (27) Carte de visite [or CDV] of Queen Victoria by John Jabez Edwin Mayall — from Wikipedia.com; (28) Portrait of Queen Victoria — from Getty Images; (29) Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee — from the website PicsToPin.com; (30) April Love, painting by Arthur Hughes of the pre-Raphaelite brotherhood — from the website Tate.org.uk; (31) Portrait of Felix Pissarro by Camille Pissarro — from the website of Boston.com; (32) Windflowers 1903, by John William Waterhouse — from the website JohnWilliamWaterhouse.net; (33) Perkin Medal — from the website of ChemHeritage.org; (34) Perkin Plaque — from the website PlaquesOfLondon.co.uk; and (35) Perkin Medal — from the website of rsc.org