It’s that time of year when autumn’s foliage graces the trees, and harvest time is nigh. Children anticipate Halloween festivities. Plus, plans for the Thanksgiving table are already in mind. And one of the most ubiquitous ornaments for the autumn season is the pumpkin.

In case you happen to wonder about the pumpkin while waiting your turn at the pumpkin patch or picking station, here are some cool facts to keep in mind:

First, the pumpkin is native to North America. Long before Europeans settled the New World, Native Americans were already cultivating the pumpkin.

Of course, the arrival of October calls to mind Halloween. And, Halloween is almost always associated with pumpkins.

Halloween has its roots in the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, which was celebrated to mark the passage of summer into autumn. Indeed, the Encyclopedia Britannica elaborates on it further, describing the festival as “the time to placate the supernatural powers controlling the processes of nature. In addition, [it was likewise] thought to be the most favorable time for divinations concerning marriage, luck, [and] health…” Samhain was a pagan observance, so when the Celtic isles became Christian, the festival transformed into the occasion known as All Hallow’s Eve.

The term All Hallow’s Eve was used as early as the 1550s, and was understood to mean ‘all holy evening.’ Thanks to the Scots, “evening” was contracted into “e’en” — thus, by the 1740s the term Halloween stuck.

But what about the roots of jack-o’-lanterns? Vegetable carvings were part of Celtic traditions for Samhain that, in turn, carried over into All Hallow’s Eve. Old Celtic lanterns were originally carved from vegetables like turnips and potatoes (the English used beets). Candles were then placed within the carved vegetables to ward off evil spirits. Over time pranksters began carving unusual faces on the vegetables to add some good humor and levity to the practice. Then, when Scottish and Irish immigrants in America were introduced to the pumpkin, they realized that it would serve as a better vessel for carving jack-o’-lanterns because the pumpkin was larger. Thus, the Halloween ritual of pumpkin heads began.

The etymological roots of the name pumpkin is interesting as well. The French explorer Jacques Cartier is credited for being the first European to report about the pumpkin, though he called it gros melon, or ‘plump melon.’ The British, who love using Greek and Latin, then decided to apply the Greek word pepon, because it meant ‘large melon.’ Pepon further evolved into the French pompon then pompion, hence prompting the British to modify it further into pumpion. Eventually the American colonists opted for calling the pumpion by its modern name of pumpkin, because of the ease in pronunciation.

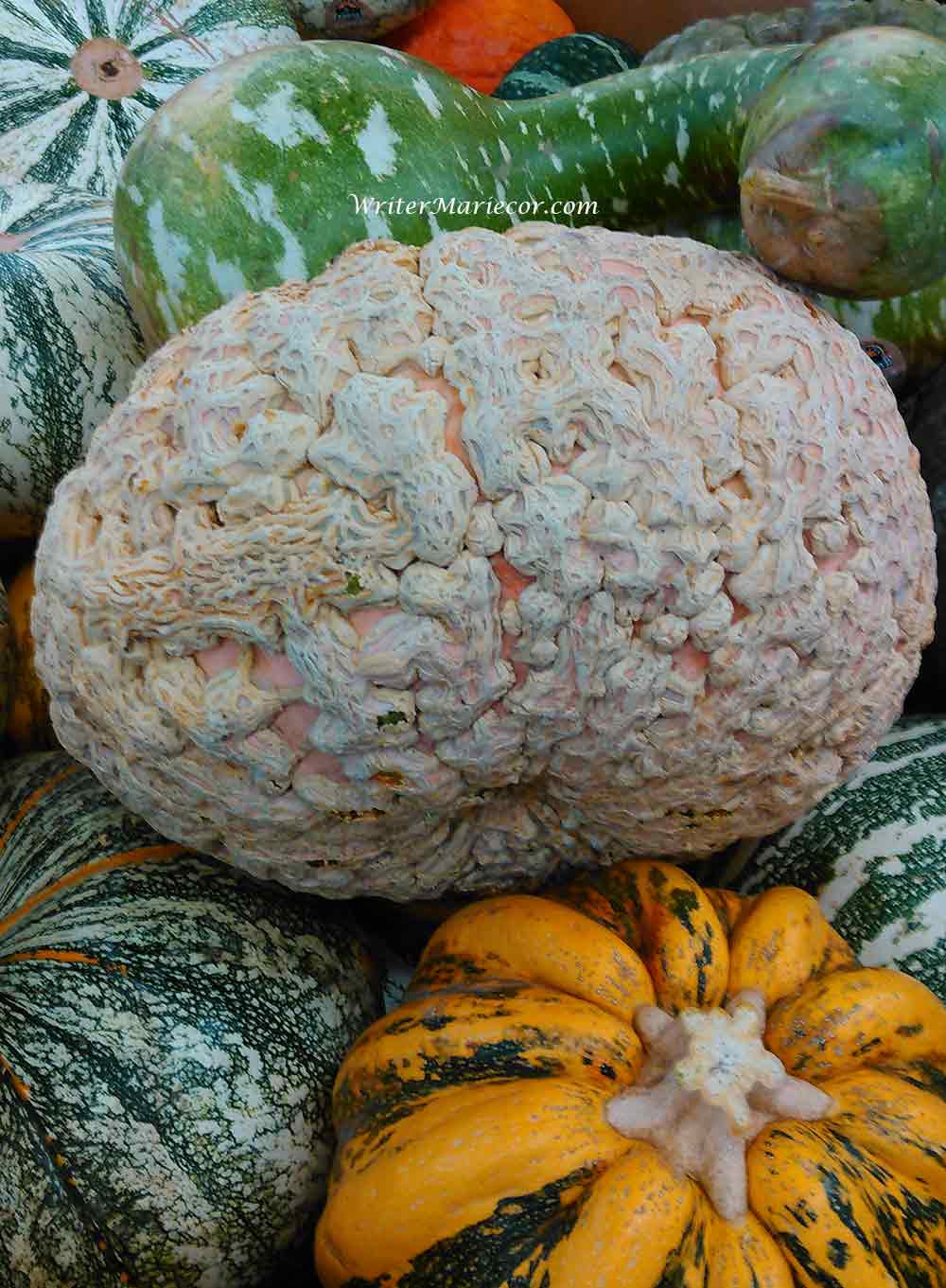

Pumpkins are members of the gourd family. They are thereby related to squash, cucumbers, zucchini, watermelons, cantaloupe, and honeydew melons.

Some folks mistakenly call the pumpkin a vegetable. However, the pumpkin is actually a fruit. It arises from the flowers of the pumpkin vine. Thanks to bees, these pumpkin flowers cross-pollinate to produce the pumpkin fruit. What’s more, the pumpkin carries seeds within it, just like other fruit such as apples, oranges, even tomatoes! Interestingly enough, there are those who advocate the pumpkin being the national fruit of the United States, particularly since it ranks as one of the most popular of American crops.

Over 80% of the US pumpkin crop is grown in Illinois. And, one particular company – Libby’s, which is a subsidiary of Nestle – produces the majority of the pumpkins that are intended for processing. Indeed, the Illinois city of Morton, where Libby’s has a pumpkin cannery, is nicknamed the ‘Pumpkin Capital of the World.’

There’s a stretch of North America called the ‘Great Pumpkin Belt.’ It’s a region with endpoints in Washington state and Nova Scotia, and is deemed the prime territory for pumpkin growing. It helps that the region can be frost-free for a time span of 90 to 120 days, which is ideal for the growth period of pumpkins. In recent years, the Ohio Valley (which is part of the Great Pumpkin Belt) has likewise become prominent in pumpkin agriculture.

Pumpkins are hardy plants. Even if some of their leaves or vines are damaged, the plant can still regenerate secondary vines as replacements. It’s no wonder then that the pumpkin was relied upon for thousands of years, proving to be a very good resource for Native Americans. The pumpkin fruit and its seeds could be consumed, not just by humans but by livestock as well. Pumpkins could likewise be dried into a type of jerky for later consumption, which was indispensable during certain nomadic journeys that Native Americans would undertake. Dried pumpkin could also be ground into a type of flour. Moreover, pumpkin flesh (like the husk before the rind shell) was dried, then woven into strips that were, in turn, used to make mats. Besides that, even the shells were utilized as storage containers, bowls, or water vessels.

As their vibrant color conveys, pumpkins are packed with carotenoids. Carotenoids are beneficial because they are antioxidants as well as precursors to vitamin A (think beta-carotene). Additionally, pumpkins are good sources of vitamin B, iron, potassium, and protein. And, they are low in fat, yet are simultaneously high in fiber.

Similarly, pumpkin seeds are treasured for their taste and their nutritional value. Historical records have shown that pumpkin seeds were held in high esteem for their medicinal properties.

Pumpkin seeds can be planted in late May or mid-June. After 90 to 120 days, the fruit will grow and then be ready for picking in October. The new batch of pumpkin fruit will then have seeds that can be saved for the following year’s planting.

Pumpkins became a mainstay for colonists. There’s a Pilgrim poem, for example, that dates from the early 1630s — which, as indicated here, communicates the significance of the pumpkin in the colonial diet:

Stead of pottage and puddings and custards and pies

Our pumpkins and parsnips are common supplies,

We have pumpkins at morning and pumpkins at noon,

If it were not for pumpkins we should be undoon.

Meanwhile, the first recognized American cookbook, published in 1796 and authored by Amelia Simmons, had two pumpkin recipes. Both entries were for puddings.

Interestingly enough, the early American pumpkin pies were quite different from our contemporary pies. For one, early American pumpkin pies were baked inside the pumpkin’s rind shell. Nowadays, pumpkin pies have pie crusts. As of this writing, the record for the largest pumpkin pie was set in 2005 by a pie that weighed in at 2,020 pounds.

Every year farmers across the US keep vying for the title of growing the largest pumpkin around. While the record for the biggest pumpkin is often broken and then reset, there is one fascinating morsel to know: many of today’s giant pumpkins owe their growth to Howard Dill.

Howard Dill, a Canadian farmer from Nova Scotia, made a name for himself for having won four consecutive times (1979 – 1982) as a giant pumpkin grower. He then patented his seeds, the Dill Atlantic Giant seeds, which are now sold worldwide. Many of today’s giant pumpkins spring from Dill Atlantic Giant seeds.

If you fancy pumpkin contests, then you might try to attend a giant pumpkin weigh-off contest near you. Check local listings for details.

Besides competitions for the largest pumpkin grown for the year, there are also tournaments for pumpkin-chucking. This is the autumn sport of hurling – colloquially nicknamed ‘chucking’ – pumpkins with anything from slingshots and catapults to trebuchets. How is the winner determined? Simple: by how far in distance the pumpkin has been chucked. There’s even a World Championship Punkin Chunkin Association (WCPCA), which hosts the oldest and largest annual tournament for hurling pumpkins. The WCPCA was first held in 1986 and has continued to grow ever since. The current Guinness world record holder for pumpkin chucking, incidentally, is attributed to a pneumatic cannon nicknamed “the Big 10 Inch,” which was able to hurl a pumpkin at a distance of 5,545.43 feet back in 2010! Should you be aching to watch the WCPCA, check the Science Channel schedule for air times – because the Science Channel has the broadcast rights to televise the tournament.

So, this autumn, while you’re being mesmerized by the jack-o’-lanterns and the season’s pies, remember the storied tapestry woven by the pumpkin.